|

Payback or Pardon?

Jesus, Joseph and the Power of Forgiveness

For Sunday September 14, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 14:19–31 or Genesis 50:15–21

Psalm 114 or Exodus 15:1–11, 20–21, or Psalm 103

Romans 14:1–12

Matthew 18:21–35

|

Joseph Mengele. |

Could you forgive Dr. Mengele, the Nazi "angel of death?" Should you forgive someone like him?

That question haunted Eva Kor, who tells her remarkable story in the documentary film called Forgiving Dr. Mengele (2007). Eva and her twin sister Miriam spent ten months in Auschwitz. Along with many other twins, they were separated from their families and subjected to Mengele's horrific "medical" experiments. After liberation by the Soviets when she was ten-years old, then living in Israel for ten years, Eva relocated to Terre Haute, Indiana in 1960 and raised a family.

Eva returned to Auschwitz for the first time in 1984. She returned for the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the camps in 1995, and on that occasion she did the unthinkable. She read aloud her personal "official declaration of amnesty" to Mengele and the Nazis. To be liberated from the Nazis was not enough, she said; she needed to be released from the pain of the past. To extend forgiveness without any prerequisites required of the perpetrators, said Eva, was an "act of self-healing." Through the act of "forgiving your worst enemy" Eva said that she experienced "the feeling of complete freedom from pain."

Many Jews were understandably outraged. In an interesting sub-plot to her film, Kor refused to extend forgiveness to or empathize with the Palestinians when she traveled to Israel. My Jewish friends tell me that Kor's film has stirred considerable controversy in their communities.

Peter was an impetuous disciple who in deserting and denying that he even knew Jesus experienced his own deep need for forgiveness. He once asked Jesus, "how many times shall I forgive my brother when he sins against me? Up to seven times?" Forgiving someone seven times is generous in the extreme. I'm sure that I've never even approximated that standard, but Jesus upped the ante and significantly expanded Peter's arithmetic of forgiveness.

Jesus told an outlandish parable about an "unmerciful servant" who received forgiveness for his own enormous debt, but then instead of extending forgiveness for a tiny debt that he was owed, he imprisoned his debtor. In the kingdom of God that Jesus announced, he instructed us to forgive not merely seven times, but seventy-seven times, or seventy times seven. The forgiveness that characterizes his kingdom, said Jesus, is beyond calculation or even comprehension.

Jesus also said that receiving forgiveness is linked to offering forgiveness. He established a law of proportionality. We can expect divine forgiveness in the measure that we extend human forgiveness: "This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother from the heart." Similarly, in the Lord's Prayer we ask God, "forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors." Our own sense of the need of forgiveness is the basis upon which we freely forgive others. We forgive because we have been forgiven. We can only long for ourselves what we lavish upon others.

|

Eva Kor returns to Auschwitz. |

Accepting God's forgiveness might be the easy part. We know, at least cognitively, that God is eager to forgive. He pardons fully and freely, and keeps no record of wrong. Human forgiveness is more complex. Our spiritual and psychological health rests, to some extent, in the hands of the person we have wronged. Forgiving your own self might be the hardest of all. As a therapist once told me, "No matter how much your friend forgives you, it won't make much difference unless you forgive yourself." Somehow the voices "inside" your head need to align themselves with the assurances from God and our neighbor that they have forgiven us. Self-imposed guilt that we can't or won't relinquish might be the last bastion of human pride, for it's humbling to admit that we really can be that bad.

Extending forgiveness is different still. Here "the numbers get crazy." Jesus asks us to forgive "seventy-seven times." Forgiveness on that scale is wildly disproportionate to the sincerity of the penitent or even the seriousness of their offense. Anyone who seeks "serial forgiveness" makes us question their motives, but Jesus says it doesn't matter — we still forgive them. Nor should the seriousness of the offense we 've suffered compromise the genuineness of our mercy. A straightforward yet radical assurance of forgiveness, offered, as Jesus says, "from the heart," can heal complex, painful and egregious wrongs we've suffered or committed.

Our popular slang captures the power of pardon: "just let it go," we say. Forgiveness of this magnitude finds its basis not only in our own sense of need but, even more sure and certain, in the character of God Himself as a fundamentally forgiving God. Paul writes, "be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you" (Ephesians 4:32). Or in this week's epistle: "Accept one another, just as God has accepted you" (Romans 14:1, 15:7).

When we forgive others we liberate them from their sins and failures, unshackle them from the chains of anxiety, guilt and shame, point them toward a future of hope instead of mire them in a past of regret, and encourage them to hit the "reset" button to begin afresh. With forgiveness we grant our offenders permission to carry on. And as Eva Kor witnessed, when we forgive others we liberate our own selves from feelings of victimization, vengeance and bitterness that will corrode our souls as surely as any wrong we have committed.

Some of the bitterest betrayals and deepest hurts we suffer come from our families. Such was the case in the story of Joseph. Joseph's brothers envied their father's favoritism, so they sold Joseph into slavery and tried to kill him. But history reversed their roles, demoting the brothers to beggars and elevating Joseph to Pharaoh's right hand in Egypt. When their fratricide was exposed, and the brothers found themselves as helpless supplicants, they fully expected that it was pay back time. But Joseph forgave them.

Joseph believed that God had a larger providential purpose for the nascent nation Israel beyond the private wrongs he had suffered: "Don't be afraid. Am I in the place of God? You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good" (Genesis 50:20). At least four times he reassures his nervous brothers, "it was not you who sent me to Egypt, but God" (Genesis 45:5, 7, 8, 9). The story concludes: "Joseph reassured them and spoke kindly to them."

|

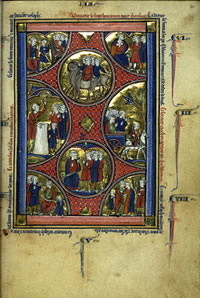

Scenes from the life of Joseph, Paris, c. 1250 – 1260, tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. |

Joseph's forgiveness of his brothers' fratricide shows how God can use our worst sins and failures in redemptive ways. This is a liberating truth if you need forgiveness. Many Christian writers have observed this principle of radical reversal whereby God uses sin and evil for our own good. St. Augustine wrote, “God judged it better to bring good out of evil than to allow no evil to exist.” According to the contemporary Frederick Buechner, “sin itself can be a means of grace.” Julian of Norwich (1342–1414), an English mystic who lived her life in total solitude, once wrote that “sin will be no shame but an honor.” Similarly, Anthony deMello writes that “repentance reaches fullness when you are brought to gratitude for your sins.” Finally, St. Augustine again, who wrote, “even from my sins God has drawn good.”

Frederic Luskin, co-founder of Stanford University's "Forgiveness Project," says that forgiveness "reduces anger, hurt, depression and stress and leads to greater feelings of optimism, hope, compassion and self confidence." Luskin has conducted numerous workshops and research projects on forgiveness. He's worked with a wide variety of people in corporate, medical, legal and religious settings. In his book Forgive for Good, Luskin elucidates what Eva Kor experienced and what Jesus taught, that in forgiving we can become "heroes instead of victims in the stories we tell."

For further reflection:

* Is there someone you need to forgive? Perhaps yourself? Maybe a family member?

* Consider the consequences of not forgiving.

* Do you find it harder to extend or to receive forgiveness? Why?

* Can or should we relate the Gospel text of forgiveness and the story of Joseph to the 9-11 anniversary?

* What are the "sticking points" in extending and receiving forgiveness?

* A favorite book on the subject is by Lewis Smedes, Forgive and Forget; Healing the Hurts We Don't Deserve

Image credits: (1) Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project; (2) the Dallas Morning News; and (3) The J. Paul Getty Museum.