Science or the Psalms?

A God Who Sees, Hears, and Acts

For Sunday April 6, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 2:14a, 36–41

Psalm 116:1–4, 12–19

1 Peter 1:17–23

Luke 24:13–35

|

Francis Collins. |

A few weeks ago Francis Collins spoke to a standing room only crowd at Stanford University about his Christian faith. Back on June 26, 2000, the medical geneticist Collins stood next to President Bill Clinton in the East Room of the White House, where they announced to the world that the Human Genome Project had completed a first draft of all 3.1 billion letters of the DNA code. As head of the project, Collins had managed over 2,000 scientists in 20 genome centers in six countries. In his recent book The Language of God, Collins remembers that day in the White House as a celebration of a stunning scientific achievement, but also as "an occasion of worship." For Collins, rigorous science nourished a robust faith.

Not everyone draws the same conclusions from the "book of nature." In her book The Sacred Depths of Nature, the eminent cell biologist Ursula Goodenough recalls a camping trip when she was about twenty years old: "I found myself in a sleeping bag looking up into the crisp Colorado night. Before I could look around for Orion or the Big Dipper, I was overwhelmed with terror. The panic became so acute that I had to roll over and bury my face in my pillow. . . When I later encountered the famous quote from physicist Steven Weinberg—'The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless'—I wallowed in its poignant nihilism. A bleak emptiness overtook me whenever I thought about what was really going on out in the cosmos or deep in the atom." Later in her book she tries to sweeten this bitter apple by making a case for religious naturalism.

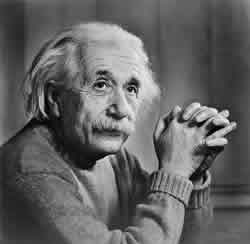

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) took a mediating position and appealed to Cosmic Awe. Einstein was irreligious in the sense that he spurned all religious institutions, never attended worship services or prayed, rejected all dogmatic theology (eg, miracles, the afterlife, or prayer), did not believe that God was in any sense personal, and was a strict determinist.

Nevertheless, Einstein thought of himself as religious in the sense of humility and awe at the mystery, rationality and complexity of the cosmos. "The eternal mystery of the world," he said, "is its comprehensibility." For Einstein, the mysterious book of nature betokened some superior intelligence: "I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings." Thus, Einstein repudiated those whom he called "the fanatical atheists" who tried to claim him for their cause. About a year before he died he wrote in a letter that he understood himself to be a "deeply religious unbeliever."

|

Ursula Goodenough. |

Interestingly enough, the psalmists depict something like what Goodenough experienced on her camping trip. It's not an uncommon human experience. The psalmists describe what a Stanford professor once shared with me over lunch, how sometimes it feels like we don't even have a relationship with God. Job despaired that God hid his face from him (Job 13:24, Psalms 88:14, 89:46). Others cry bitterly that He doesn't answer when they call (Psalm 22:2), that He is stone deaf to their cries (Psalm 28:1), that God stands “far off” from us (Psalm 10:1), and that He even forgets us due to some sort of divine amnesia (Psalms 13:1, 44:24).

The Psalms also describe something like Einstein's awe, as when they affirm that "the heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands" (Psalm 19:1). But the psalmists go far beyond Goodenough's despair or Einstein's awe. They make the stupendous claim that the transcendent God who flung the 100 billion galaxies into space, each one with 100 billion stars, is like an attentive mother or a tender father who cares for each and every human being. Despite any feelings to the contrary, He hears our every cry for help, and intervenes to act for our good.

I love the LORD, for he heard my voice;

he heard my cry for mercy.Because he turned his ear to me,

I will call on him as long as I live.The cords of death entangled me,

the anguish of the grave came upon me;

I was overcome by trouble and sorrow.Then I called on the name of the LORD:

"O LORD, save me!"The LORD is gracious and righteous;

our God is full of compassion.The LORD protects the simple hearted;

when I was in great need, he saved me.Be at rest once more, O my soul,

for the LORD has been good to you.For you, O LORD, have delivered my soul from death,

my eyes from tears,

my feet from stumbling,that I may walk before the LORD

in the land of the living. (Psalm 116:1–9, NIV)

The Psalmist affirms exactly what Einstein denied, that God speaks and acts, that He loves and He listens, that He knows my name and will act on my behalf.

When I was in seminary my classmate Phil coined a word for the sort of religious faith that has a firm and unwavering belief in a tame and innocuous divinity. It's a sort of faith that doesn't expect that God will meddle in human affairs, intercede in your life, providentially guide human history, care for a loved one, heal the hurts we suffer, make something out of nothing, or do the impossible. Phil characterized this sort of tepid faith as "functional deism." Functional deism never denies the existence or reality of God, but it also never expects His decisive action in your personal affairs. Functional deism is more like the vague religious naturalism of Goodenough and Einstein rather than the vibrant faith of Collins or the Psalms.

|

Albert Einstein. |

Hagar, the Egyptian slave of Abraham and Sarah, once felt badly alone and abandoned (Genesis 16). Sarah was barren, so she commanded Abraham to produce a child with Hagar. He consented, was successful, and Ishmael was born. But when “Sarah treated Hagar harshly,” the powerless and pregnant maid fled. In the tenderness of God, “the angel of the Lord found her” in the desert by a spring of water, and promised her that God had, in fact, heard her cries for help and given heed to her affliction. Her son's name would always remind her of this, for Ishmael means “God hears.” Hagar worshipped Yahweh, saying, “Thou art a God who sees me,” and named the well there Beer Lahai Roi, “the well of the Living One who sees me.”

The psalmists remind us of what Hagar discovered, that God does see us and love us, that regardless of how we might feel, He does hear our cries. “I love the Lord, for He heard my voice; He heard my cry for mercy” (Psalm 116:1). He has not, ultimately, hidden his face from me (Psalms 22:24, 38:9, 139:15). In the prophetic tradition, Isaiah is quite insistent, challenging Israel, “Why do you say, O Jacob, and assert, O Israel, ‘My way is hidden from the Lord, and the justice due me escapes the notice of my God’?” (Isaiah 40:27).

And so in the wake of Easter, and after Collins's lecture at Stanford, I made a mental note to myself: the God of science is one thing; the God of the psalmists is quite another. With my seminary friend Phil I pray, "Lord, save me from the tepid faith of functional deism. Just as you hear my voice, please let me hear yours."

Image credits: (1) Chinese Medical and Biological Information website, http://cmbi.bjmu.edu.cn; (2) The American Association for the Advancement of Science; and (3) Hellenica website, www.mlahanas.de.