Betwixt This World and That of Grace:

Fourth Sunday in Lent 2008

For Sunday March 2, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

1 Samuel 16:1–13

Psalm 23

Ephesians 5:8–14

John 9:1–41

|

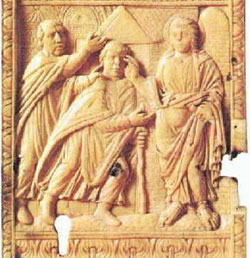

Jesus heals the blind man, ivory carving, 400 AD.. |

A few years ago Sister Ann surprised me in our therapy session with an abrupt question: "Why do you pastor-types place yourselves on such a pedestal? Why are you so shocked at your faults and failures? Why not come down and join the human race?" Since I had never viewed myself this way, it became clear that I was blind to something about myself that in her professional judgment was obvious.

I think that among other things Sister Ann was trying to help me to understand the rather enigmatic punch line of Jesus that concludes the Gospel reading for this week: "For judgment I have come into this world, so that the blind will see and those who see will become blind." When some Pharisees then asked if they themselves were blind, Jesus responded, "If you were blind, you would not be guilty of sin; but now that you claim you can see, your guilt remains" (John 9:39-41).

In the Christian scheme of things, one of the most dangerous spiritual places you can live, oddly enough, is in the deluded notion that you are a fully-sighted person. Conversely, the healthiest place to live is not only to acknowledge your spiritual blindness, sin, failure, contradictions, complicities, and ignorance, but to embrace that place as a good place to live. In acknowledging our blindness, we see; by insisting that we see fully and rightly, we remain blind.

John 9:1–41 recounts the healing of a beggar who was blind from birth. But the details of the miracle itself comprise only about one third of the narrative. Most of the story revolves around the disputes that the miracle provoked, followed by Jesus's punch line. There are so many fascinating details that merit attention: precise descriptions about spit, mud, and the interrogation of parents that characterize an eyewitness account; the casual disinterest about Jesus on the part of the man who received the miracle; the inexcusably cruel insinuation by the disciples that somehow human misfortune (the beggar's blindness) was an act of divine punishment; the inherent skepticism and suspicion surrounding the plausibility of a genuine miracle (so much for the ancient's gullibility about miracles!); the complex factors at play that can prevent a miracle from evincing genuine faith; and the interactions amongst the characters in the larger drama—Jesus, his disciples, the blind beggar, his parents, the religious elite, and even the neighborhood community.

The professional clergy made all the wrong moves in this story. They refused to believe eye-witness accounts of the miracle. They were more concerned to maintain ritual righteousness about Sabbath-keeping than to love another human being and rejoice in his wholeness. They blabbered pious cliches. They scapegoated the victim and "hurled insults" at him. They condescendingly claimed a spiritual elitism that intentionally humiliated the beggar. They demonized him as a "sinner." As they threw him out of the synagogue their rage exploded, "How dare you lecture us!" At that their own tragic blindness was confirmed, and we learn that it was their spiritual blindness, and not the physical blindness of the beggar, that forms the central plot of the story.

|

Healing of the blind man by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1308-1311), tempera on wood. |

Of course, acknowledging your own spiritual blindness can be embarrassing, painful, and threatening. To confess your own groping darkness and howling demons, your frustrations, fears, and failures, unnerves us. And as unsettling as that confession is to make to your own self, there is the added anxiety of what others might say, think, or do. We know from experience (and from the disciples and the clerics in this Gospel story) just how cruel and condescending, how derogatory and dismissive, people can be towards the blind. Some people will kick you when you are down. We shoot the wounded.

But Sister Ann knew what Jesus taught in this story, that healthy people embrace their fallenness and somehow make their peace with it. That's far different than self-pity, self-loathing, or rationalizing it or invoking it as an excuse. Spiritually-sighted people recognize that acknowledging their blindness is an act of liberation not a confession of bondage. Perfection is an awful and oppressive burden to bear. Only when we identify our symptoms can we experience a cure.

George Herbert's (1593–1633) poem Affliction (IV) is a masterful confession of one's own blindness and inner struggles. It's a perfect prayer for the Lenten season.

Broken in pieces all asunder,

Lord, hunt me not,

A thing forgot,

Once a poor creature, now a wonder,

A wonder tortur’d in the space

Betwixt this world and that of grace.My thoughts are all a case of knives,

Wounding my heart

With scatter’d smart,

As wat’ring pots give flowers their lives.

Nothing their fury can control,

While they do wound and prick my soul.All my attendants are at strife,

Quitting their place

Unto my face:

Nothing performs the task of life:

The elements are let loose to fight,

And while I live, try out their right.Oh help, my God! let not their plot

Kill them and me,

And also thee,

Who art my life: dissolve the knot,

As the sun scatters by his light

All the rebellions of the night.Then shall those powers, which work for grief,

Enter thy pay,

And day by day

Labour thy praise, and my relief;

With care and courage building me,

Till I reach heav’n, and much more, thee.

Herbert, Sister Ann and Jesus all point us in the same direction this Lenten season: the journey toward the light begins when we acknowledge the dark.

|

Jesus healing the blind man, © Jill K H Geoffrion, www.jillkhg.com. |

We can confess our blindness with confidence and no longer fear our fears (Manning). That's because in the words of the English mystic Juliana of Norwich (1342–1414), before God our "sin will be no shame but an honor." How so? "For He sees sin as sorrow and pain to His lovers to whom, for love, He assigns no blame. . . . Our failures do not prevent Him from loving us."

For further reflection:

* What connections can you make between physical and spiritual blindness?

* Who do you identify with in the story of John 9?

* Contemplate Herbert's line about being a "tortured wonder caught between this world and that of grace."

* Why do we find it so hard to confess our own faults and failures, and to accept the same in others?

* See Brennan Manning, The Ragamuffin Gospel.

Image credits: (1) FaithCentral.net.nz; (2) Web Gallery of Art; (3) © Jill K H Geoffrion, www.jillkhg.com.