Wading Into the Waters:

The Baptism of Jesus

For Sunday January 13, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 42:1–9

Psalm 29

Acts 10:34–43

Matthew 3:13–17

|

Mosaic dome in the Arian Baptistry in Ravenna, Italy, 5th century. |

In The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), a film directed by Martin Scorsese and based upon the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, we watch a very human Jesus. He confesses his sins, he fears insanity, he wonders if he's merely a man, and he anguishes over the people he didn't heal.

In his "last temptation," during his execution Jesus has a hallucination sent by satan. He imagines what his life might have been like if he had chosen the path of an ordinary man. He imagines himself marrying Mary Magdalene, growing old, and having kids. But then he sees the disciples reproaching him for abandoning his special mission, and through their reproach he returns to consciousness to accomplish his final suffering, death, and resurrection.

Many Christians were outraged by Scorsese's film and considered it blasphemous. Blockbuster Video even refused to carry it. What seemed to bother many Christians was the suggestion that Jesus was fully and truly human, that he was a person who experienced trials and temptations, faults and failures, just like we do — torment, doubt, loneliness, questions, fantasies, confusion, despair, erotic dreams, and, in his final hours, feeling abandoned by God Himself.

With his baptism Jesus fully identified with fallen humanity. Matthew has already tipped his hand in this regard. On page one of his gospel he lists forty-two men in Jesus's genealogy, then four women with unsavory pasts. Tamar was widowed twice, then became a victim of incest when her father-in-law abused her as a prostitute (Genesis 38). Rahab was a foreigner and a whore who protected the Hebrew spies by lying. Ruth was a foreigner and a widow, while Bathsheba was the object of David's adulterous passion and murderous cover-up (Matthew 1:1–17). These women stick out like a sore thumb; but they nevertheless formed part of Jesus's family of origin.

On page two, Matthew then honors the pagan magi from Persia who worshipped Jesus with their gifts. Page three brings us to his baptism. To air brush this fully human Jesus is to fall prey to something like the second-century heresy of docetism (from the Greek dokeo, "to seem or appear") that claimed Jesus only "seemed" human. Surely he couldn't have been polluted by our material existence! In trying to "protect" Jesus from a genuine human nature, we do the exact opposite of what he himself does in his baptism; instead of insulating himself from us, he fully participates with us.

Russian icon of Jesus's baptism, 15th century. |

After living in total obscurity his entire life, in his late twenties Jesus left his family in Nazareth and burst onto the public scene by joining the movement of his eccentric cousin, John the Baptizer. Perhaps Jesus submitted himself to John as a disciple to a mentor. John might have been part of the apocalyptic Jewish sect of Essenes who opposed the temple in Jerusalem. By any measure, John the Baptizer was a prophet of radical dissent; his detractors had good reasons to say that he acted like he had a demon (Luke 7:33).

Whereas his father was a priest in the Jerusalem temple, John fled the comforts and corruptions of the city for the loneliness of the desert. There he dressed in animal skins and ate insects and wild honey. Living on the margins of society, both literally and figuratively, he preached a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins, which is to say that he announced a message of both indictment and invitation: "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!" Later, Jesus repeated John's exact words to announce his own public ministry (Mark 1:15). Contrary to what we might have expected from such an ascetic man with an austere message, the Gospels say that people flocked to John.

John's preaching in the Judean desert and baptizing in the Jordan river confronted both the religious and the political powers of his day. Imperial Rome beheaded him when John rebuked Herod for sleeping with his brother's wife (Matthew 14:1–12). The temple establishment in Jerusalem, which claimed a gate-keeper monopoly on mediating God's forgiveness to people, didn't like him preaching from the periphery either. John castigated these religious authorities as a "brood of vipers" (in one translation, "snake bastards"). The religious experts, said Jesus, spurned John's call to baptismal repentance, and in so doing "rejected God's purpose for themselves" (Luke 7:30).

Instead of cooperation, accommodation, or resignation, John challenged these religious and political powers with his anti-establishment message of "protest and renewal." By joining John the Baptizer's fringe movement, Jesus did likewise.

With some important stylistic differences, all four Gospels tell the story of Jesus's baptism by John: "When all the people were being baptized, Jesus was baptized too. And as he was praying, heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: 'You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased'" (Luke 3:21–22 = Mark 1:9–11= Matthew 3:13–17; John 1:29–34).

No wonder that after this radical rupture with his family and conventional society by identifying with the desert troublemaker, eventually Jesus's own family tried to apprehend him. The village of Nazareth tried to kill him as a deranged crackpot (cf. Mark 3:21, Luke 4:29, John 7:5).

Why did Jesus the greater submit to baptism by John the lesser? Did he need to repent of his own sins? The earliest witnesses of his baptism asked this question, because in Matthew's Gospel John the Baptizer tried to deter Jesus: "Why do you come to me? I need to be baptized by you!" John insinuates that Jesus was not getting baptized for his own sins.

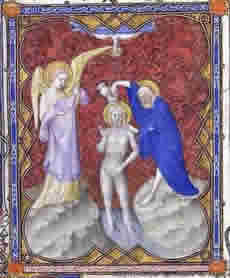

|

Unknown Illustrator of "Petites Heures de Jean de Berry," 14th century. |

But even a hundred years later Jesus's baptism made some Christians feel uneasy. In the non-canonical Gospel of the Hebrews (c. 80–150 AD), for example, Jesus denies that he needs to repent. He seems to get baptized to please his mother: "The mother of the Lord and his brothers said to him, 'John the Baptist baptizes for the forgiveness of sins; let us go and be baptized by him.' But he said to them, 'In what way have I sinned that I should go and be baptized by him? Unless, perhaps, what I have just said is a sin of ignorance.'” Others have suggested that Jesus set an example for us, that just as he was baptized, we too should be baptized.

Jesus's baptism inaugurated his public ministry by identifying with what Luke describes as "all the people." He allied himself with the faults and failures, pains and problems, of all the broken and hurting people who had flocked to the Jordan River. By wading into the waters with them he took his place beside us and among us. Not long into his public mission, the sanctimonious religious leaders derided Jesus as a "friend of gluttons and sinners." They were surely right about that.

With his baptism Jesus openly and decisively declared that he stands shoulder to shoulder with me in my fears and anxieties. He intentionally takes sides with people in their neediness, and declares that God is biased in their favor: "For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet was without sin. Let us then approach the throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in our time of need” (Hebrews 4:15–16, NIV). God's abundant mercy, Jesus declared, is available directly and immediately to every person; it's not the private preserve doled out by the temple establishment in Jerusalem.

Jesus's baptismal solidarity with broken people was vividly confirmed by divine affirmation and empowerment. Still wet with water after his cousin had plunged him beneath the Jordan River, Jesus heard a voice and saw a vision—the declaration of God the Father that Jesus was his beloved son, and the descent of God the Spirit in the form of a dove. The vision and the voice punctuated the baptismal event. They signaled the meaning, the message and the mission of Jesus as he went public after thirty years of invisibility — that by the power of the Spirit, the Son of God embodied his Father's unconditional acceptance of all people without exception.

For further reflection:

* Why do you think Jesus submitted himself to John's baptism?

* Cf. John Howard Yoder on John the Baptist: "To repent is not to feel bad but to think differently."

* Cf. Isaiah 42:3: "A bruised reed he will not break/and a smoldering wick he will not snuff out."

* Consider the functions of water to heal, cleanse, nourish, quench thirst, etc.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Christus Rex Project Art Gallery; and (3) Maurice Lamoreaux, The Illustrated Bible.