Strange People, Strange Places:

The Geography of Salvation

For Sunday October 14, 2007

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 29:1, 4 –7 or 2 Kings 5:1–3, 7 –15c

Psalm 66:1–12 or Psalm 111

2 Timothy 2:8–15

Luke 17:11–19

|

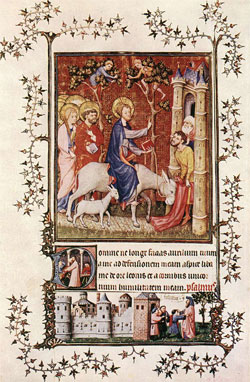

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, by Andreas Heidrich |

In my Bible the Old Testament runs to about 1300 pages. I suspect that many readers who have vowed to read straight through the entire Scriptures bogged down somewhere before the New Testament. I know that I have. To simplify Yahweh's long drama of salvation with his elect people Israel, we could say that it revolves around two major acts in two different places.

First, after 430 years of slavery, God liberated Israel from Egypt in the Exodus some time around 1400 BC. Then, eight hundred years later, there is tragic Exile to Babylon in the year 586 BC. These seminal events of exodus and exile reverbate throughout both the Old and New Testaments as two paradigms or models of the way God works in human history, and even in our own personal histories.

The Exodus is a drama of liberation from oppression and exploitation, of miraculous deliverance, of God's mighty acts of power in regal display, of His dramatic intervention to shatter the enemy, work wonders, and break the powers of bondage. No wonder it's mentioned throughout the Bible as a reminder of God's power to save, and celebrated at Passover even today by Jews. The Psalmist for this week proclaims, "How awesome are your deeds!" (Psalm 66:3). The Exodus story reminds us that we have every reason to hope and pray for God's dramatic acts of salvation, both in the world at large and in our personal lives.

But with the Exile the geography of salvation changed. For the ancient Hebrews, the destruction of Jerusalem and deportation to pagan Babylon was unthinkable, beyond comprehension. What had happened? Where were Yahweh's mighty acts of power? Was not Israel God's inviolable and elect people, and if so how could He surrender them to a pagan nation? Exile to Babylon began a period of subjugation, servitude, banishment and captivity. It signaled failure, isolation, loneliness, and even punishment. Certainly it meant despair, for the elite Jews who were deported and for the common people of the land left behind in the rubble of Jerusalem.

How was a Hebrew deported to Babylon, torn from home and everything familiar and dear, to understand his exilic life? In the lectionary this week the prophet Jeremiah offers advice that few people probably wanted to hear. Writing from besieged Jerusalem, he sent a letter to the exiles who had been deported to Babylon. Here's what he wrote (Jeremiah 29:4–7):

This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says to all those I carried into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon: "Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the Lord for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper."

Jeremiah tells the exiles to embrace their disaster rather than to resist it. There was salvation in the strange place of Babylon as well as in the familiar place of Israel. He tells them to let go of their past and to accept their new circumstances, however unthinkable. He says that contrary to all appearances, despite the foreign geography, at that moment in Yahweh's story of salvation, they were better off in pagan Babylon than left behind in holy Jerusalem. God was still working, only now in the most unlikely of ways and in the most improbable of places.

|

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, 12th century Germany. |

Celebrating God's mighty acts of power, His decisive miracles of deliverance, is easy. Who doesn't long for a personal Exodus, punctuated by a divine exclamation point, whether that be for work, at home, a marriage, finances, children—the list is nearly endless. But we know that sometimes things don't work out as we wish, or as we think they should, or as we pray. History can take a bitter turn. Catastrophe can overtake us, sometimes of our own making, other times for no apparent reason at all.

Living in exile, far from home, in a strange space or place, bereft of all one considers good and familiar, is difficult. Living in exile demands revised expectations. Courage to believe that God is still at work, no matter how bleak the circumstances. Learning a new language and grammar, much as the Jews settling into Babylon learned a new tongue, to articulate your lived experience. Perseverance over the long haul.

Living in exile also requires hope about the future, no matter how dark the present. That, too, was part of God's message (29:11): "For I know the plans I have for you," declares the Lord, "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future." That future was far off for those Babylonian exiles, seventy years and two generations before the Persian king Cyrus would rout the Babylonian regime and permit the Hebrews to return home (a story told in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah). Hope for the future is also an admission that we can't have it all now in the present. Some of the exiles never returned home.

It's easy to imagine that Yahweh, who called Israel as His elect people, worked only in Israel, on "home turf." That's not true. Jeremiah reminds us that He's at work always and everywhere, in Exodus from Egypt to be sure, but also in Exile to Babylon. God is at work not only in strange and foreign places like Babylon, but also in foreign people like Namaan.

Naaman epitomizes the foreign "outsider" for several reasons. He was a military officer from pagan Aram (= Syria), a major enemy of Israel. The narrator praises Naaman in glowing terms: "He was a valiant soldier, a great man in the sight of his master and highly regarded." Then he ads a stunning detail: "through Naaman the Lord had given victory to Aram." God gave victory to Israel's enemy through a pagan officer? Yes. Finally, Naaman had a skin disease (often wrongly translated as "leprosy"). This disease, as Frank Spina notes in his book The Faith of the Outsider, might have caused Naaman some medical problems, but his real complications were social, religious, and moral, for people with such "impurities" were stigmatized as ritually unclean and therefore excluded from God's community and its worship (2 Kings 5).

|

The Cleansing of Naaman by the Prophet Elisha, Master of the Baptist, c. 1409. |

This "great man" (2 Kings 5:1) embarked on a state visit with opulent gifts to visit the king of Israel, only to encounter a nameless "little girl" from Israel who advised him to seek healing from the Hebrew prophet Elisha. The irony is unmistakable and Naaman's response is predictable; when this anonymous Hebrew child instructed the renowned military officer not to seek help from the corridors of political power but from a religious prophet who told him to wash himself seven times in the Jordan River, he was incensed. But Naaman obeyed, he was healed, and then he was converted: "Now I know that there is no God in all the world except in Israel."

Finally, he took some dirt from Israel back to Aram, "for I will never again make burnt offerings and sacrifices to any other God but the Lord." Perhaps Naaman wanted to establish a portable "sacred space" back home. Although back home in Aram he continued to worship in the temple of the deity Rimmon, Naaman asked for advance forgiveness for that compromise, and declared his fidelity to Israel's Yahweh. So again we see God's mysterious means—Naaman the outsider joined the insider community, a nameless little girl advised a military leader, and the prophetic power of Elisha subverted social and political conventions.

God works in strange places like Babylon. We should never forfeit the hopes, dreams and prayers for Exodus deliverance, but neither should we forget the Exile motif of living in banishment. Human experience assures us that we will need the latter paradigm as well as the former. There are periods of darkness and gloom when we feel far from home, and it's natural to pray for Exodus deliverance. Christian maturity means putting one foot in front of another, and remembering that Yahweh is no less present in exilic darkness than in exodus deliverance.

God works in strange people like Namaan. Anyone who considers themself an "insider" should beware of presumption: "God, I thank you that I am not like all other men" (Luke 18:11). To our peril we ignore, shun, and vilify the "foreigner" or the "outsider" as strange, dangerous and unclean. We smugly imagine that we possess the truth as few others do, rather than humbly ask God in His mercy that we might be transformed by His truth. Rather than considering solidarity with the lost, the lonely, and the outsider a privilege that enriches our lives, we construe the Biblical narrative in a narcissistic manner to serve our own petty ends. Paul, the consummate Christian "insider," even contemplated the real and harrowing possibility of his own banishment to "outsider" perdition (1 Corinthians 9:24–27).

For further reflection:

* What have been your experiences of exodus deliverance? Of exilic darkness?

* When have you discerned God working in strange places or people?

* In this week's Gospel Jesus heals ten lepers (Luke 17:11–19). Only one leper returned to give thanks—a Samaritan foreigner who experienced not only healing but salvation. The outsider-foreigner was thus the "hero" of the story.

* Cf. the new book by Mother Theresa in which she describes her own long periods of exilic darkness: Come Be My Light (2007).