How Long, O Lord?

Why the Delay in Divine Intervention?

For Sunday September 23, 2007

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 8:18–9:1 or Amos 8:4–7

Psalm 79:1–9 or Psalm 113

1 Timothy 2:1–7

Luke 16:1–13

|

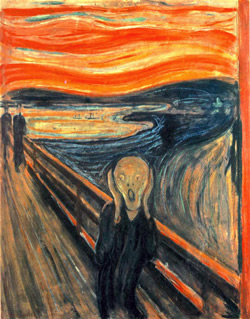

Edvard Munch, The Scream. |

After I finished grad school I moonlighted at a Presbyterian church as a part-time pastor for home visitation. The very first person I visited that July was a widow named Jan. I could barely believe her story as I sat in her living room. Jan had just lost her husband, her two sons, her father, an uncle, and a nephew in a single boating accident on a lake in Minnesota. Six loved ones had perished in a freak storm on their annual fishing trip.

As I drove home that night I thought of the cry of the psalmist: "How long, O Lord?" (79:5). He'd had enough; his patience and piety were spent. Why the delay in divine intervention?

The prophets ask the same question in slightly different ways. Doesn't God care that the rich "trample the needy" (Amos 8:4)? Why doesn't he do something? During Israel's national catastrophe Jeremiah bitterly complained that there was "no balm in Gilead, and no physician there. Why is there no healing for the wound of my people?" His repeated prayers for divine deliverance ended with a reluctant concession: "the harvest is past, the summer has ended, and we are not saved" (Jeremiah 8:20, 22).

A thousand years after the psalmist, John asked the very same question. Banished to the remote island of Patmos for his faith, John pictured Christians who had been slaughtered by the Roman government crying out, "How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?" (Revelation 6:10). How long before the emperor and demagogue Domitian (81–96) met divine justice, that despot who persecuted Jews and Christians, who signed his imperial documents "god and lord," and whose coins proclaimed him "father of the gods?"

We have our modern equivalents that provoke these ancient questions. My wife has a second grader in her class whose father was electrocuted while repairing the family television. In her art work she still draws pictures of her dad. At her Bible study, Ellen bluntly described the tragic death of her husband: "Tim and I had a car wreck; they brought me home and took him to the mortuary." Down the street our neighbor with pre-school triplets struggled as a single mom after her husband left her; now she has brain cancer. How long will anguished cries from Darfur meet stony silence? How long will Iraqi civilians suffer so innocently while suicide bombers murder with such impunity?

How long, O Lord? The question might sound impious with its impatience, doubt and discouragement, but it echoes through the Scriptures nearly a dozen times.1

|

Iraqi mother. |

The most honest answer to the psalmist's question might also be the least satisfying: we don't know. We don't know why God doesn't intervene more dramatically, more often, and more decisively in human affairs. If God is perfectly good wouldn't he want to do something about all the suffering in the world? And if He's all powerful surely he's able to do something about suffering. Even admitting all that we don't know (which is considerable), and that God's ways are not our ways (Isaiah 55:8), it still seems like a world with less human suffering and more divine deliverance would be a better world. So, we don't know why the delay in divine intervention.

Admitting our ignorance reminds us that we don't have to understand everything, or answer every difficult question. Paul said that often we can only see “through a glass darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12). Some of the suffering we experience is inscrutable, and some of it admits no solution, no matter how much time, money, effort, prayer, or therapy we throw at it. Augustine (354–430) advised that sometimes "the secrets of heaven and earth still remain hidden from us" and therefore we must "rest patiently in unknowing."

In addition to making peace with our ignorance, the ire of the psalmists encourages us to acknowledge our emotions. Rather than deny, soft pedal, or sugar coat the hell and heartache we sometimes experience, they vent their emotions with brutal honesty. By extension, they invite us to do the same. One entire book of the Bible, for example, is simply called Lamentations. We needn't repress our emotions, silence difficult questions, or adopt a spirituality of artificial optimism, pious platitudes, and superficial cliches, all of which reflect a lack of authenticity and honesty about how we feel about what we experience.

The emotional candor of the psalms has led people to compare them to mirrors in which we see our own reflection. Athanasius (296-373), a bishop in Alexandria, Egypt, called the psalms "a mirror of the soul of every one who sings them; they enable him to perceive his own emotions, and to express them in the words of the Psalms. . . . In its pages you find portrayed man's whole life, the emotion of his soul, and the frames of his mind." John Calvin (1509–1564) recommended the psalms for the same reason, "for there is not an emotion of which one may become conscious that is not represented as in a mirror. Or rather, the Holy Spirit has here drawn to the life all the griefs, sorrows, fears, doubts, hopes, cares, perplexities, in short, all the distracting emotions with which the minds of men are wont to be agitated."

Admitting our ignorance and acknowledging our emotions needn't lead to despair. Sometimes we must "wait patiently" for the Lord (Psalm 37:1, 7–8). Merely waiting doesn't sound very spiritual or revolutionary, but waiting can work its magic if we let it.

|

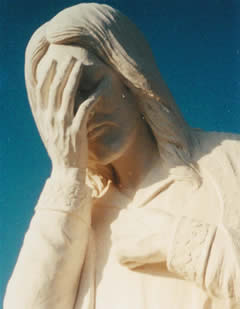

Jesus weeping. |

A few years after moving to Fuller Seminary, professor Lewis Smedes fell into a deep depression that "made a hash of my relationship with God, and pushed me into a dark night of the soul. My experience was, from start to finish. . . . a hellish sense that God had abandoned me." He was alienated from his colleagues, his family, his own self, and, on top of it all, he felt like a tremendous hypocrite. "I did not know where God was during this time. I only 'knew' that wherever he was, he was not with me. But I was wrong. He was with me because he was in Doris, and Doris was with me. What did she do? She did nothing. Nothing but wait. And wait. And wait. God came back to me on the strength of her power to wait for me. Never before had I known the saving power of waiting."

Smedes was honest about his emotions. He acknowledged his ignorance. He and his wife Doris also waited, and eventually they testified how "God came back to me at the very moment that I had reached ground zero in my hopelessness."

For further reflection:

* What have been your darkest days, and how did you deal with them?

* What did you learn about yourself and God from your dark days?

* Why are we tempted by pious platitudes instead of honesty about our doubts and emotions?

* Are you surprised at the cries of the psalmists and prophets?

*

See DA Carson, How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006 second edition).

* Lewis Smedes, My God and I (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003)

[1] Psalm 6:3, 13:1, 35:17, 80:4, 89:46, 90:13, 94:3, Isaiah 6:11, Habakkuk 1:2, Zechariah 1:12, and Revelation 6:10.