Amo Ergo Sum:

I Love, therefore I Am

For Sunday November 5, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Ruth 1:1–18 or Deuteronomy 6:1–9

Psalm 146 or Psalm 119:1–8

Hebrews 9:11–14

Mark 12:28–34

|

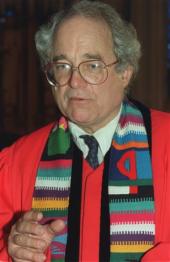

Will Campbell. |

From the time he was seven years old Will Campbell (b. 1924) wanted to be a preacher. After ordination at the age of seventeen, for twenty years he devoted himself to the civil rights movement based upon his understanding of the Gospel. He had few peers. In 1957, for example, he was one of four people who escorted the nine black students who integrated Little Rock's Central High School; and he was the only white person to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. But something was amiss.

As he matured, Campbell disovered how readily he hated those who hated, how easy it was to oppress the oppressors. Strange, he thought, how he enjoyed thinking that God hated all the same people that he hated. He had the uneasy feeling that he had created God in his own image, and after his likeness. Through a series of encounters with unlikely "teachers," he came to admit that after twenty years in ministry he had become little more than a "doctrinaire social activist." He had subverted the indiscriminate love of God for all people without conditions, limits, or exceptions into a ministry of "liberal sophistication." Acting upon these convictions, he started sipping whiskey with the Ku Klux Klan and befriended the Grand Dragon of North Carolina, J.R. "Bob" Jones. At that point the hate mail started coming from the left instead of the right.

Campbell's mistake was to define the Gospel by the civil rights movement (instead of vice versa). For William Sloan Coffin (1924–2006), the struggle was against the idolatry of academia. As chaplain at Yale University, Coffin observed how students at Yale “thought cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) was what it was all about, and Yale was encouraging them to think that." Like Campbell, Coffin wanted to keep the main thing the main thing: "I felt very deeply that it’s amo ergo sum (I love, therefore I am).”

|

William Sloane Coffin. |

People define themselves, shape their identities, and create their personas in any number of ways. Social liberalism and academia are only two examples. Some people define themselves by the intensity of their work and the accumulation of their wealth. For others, sports, politics, environment, sexual identity, ethnicity, or even their alma mater is what matters to them most. These identity markers then become ways that we categorize, exclude and stereotype people—"She's a techie brainiac, he's a nerd, they're liberal, and we're conservative." They also have their dark or down side. Sexual identity is a deeply human and powerful trait, but by itself reductionistic. Ethnicity is a legitimate source of pride, but the source of toxic hatred and even genocide. Hard work is admirable, but life is far bigger.

According to Jewish rabbinic tradition, there are 613 mizvot or "commandments" in the five books of Moses. In Mark's Gospel for this week an expert in the law put an obvious question to Jesus. Are some of these laws are more important than others? Which laws are peripheral and insignificant, and which ones are weighty and essential? What, exactly, defines our greatest good? These laws encompassed nearly every aspect of being human—birth, death, sex, gender, health, economics, jurisprudence, social relations, hygiene, marriage, agriculture, clothing, and certainly ethnicity (Gentiles were automatically considered impure). The purity laws of Leviticus chapters 11–26, for example, instructed the Hebrew community about clean and unclean foods, purity rituals after childbirth or a menstrual cycle, regulations for skin infections that contaminated clothing or furniture, prohibitions against contact with a human corpse or dead animal, instructions about nocturnal emissions, laws regarding bodily discharges, guidelines about planting seeds and mating animals, and decrees about lawful sexual relationships, keeping the sabbath, forsaking idols, and even tattoos.

Of all the many ways that people might define themselves, whether by social liberalism, academia, or one of the 613 commandments, Jesus responded that "the most important one is this: 'Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength' [Deuteronomy 6:4]. The second is this: 'Love your neighbor as yourself' [Leviticus 19:18]. There is no commandment greater than these." The questioner liked Jesus's answer and affirmed that these two commands were "more important than all burnt offerings and sacrifices," more important, we might say, than the 611 other commands.

|

The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, Eugene Delacroix, 1840. |

The necessary connection between claiming to love God and demonstrating that we love our fellow human beings became so embedded in the early Christian traditions that we find this teaching repeated almost verbatim by Paul (Romans 13:8–9, Galatians 5:14), by James (James 2:8), and most memorably by John: "If anyone says, 'I love God,' yet hates his brother, he is a liar. For anyone who does not love his brother, whom he has seen, cannot love God, whom he has not seen. And he has given us this command: Whoever loves God must also love his brother" (1 John 4:20–21). About a century after Mark wrote, the early Christians had a well-known and well-deserved reputation for social generosity that built bridges of community rather than walls of separation. Tertullian (AD 155–220), for example, wrote, "Our care for the derelict and our active love have become our distinctive sign before the enemy . . . See, they say, how they love one another and how ready they are to die for each other."

Then something went badly wrong for a large part of the institutional church.

In his review of Christopher Tyerman's massive new book God's War; A New History of the Crusades, Eamon Duffy comments on the profound and deeply disturbing paradox of how the good news of God's indisciminate love became a cause for violent hatred. In the crusades Catholics sanctified the slaughter of pagans, Muslims, Jews, and then, in the Fourth Crusade, even their fellow Christians when they sacked Constantinople in 1204. "Engagement in a holy war sanctified the very activity which had before been a barrier to heaven. Here, from the highest spiritual authority on earth [that is, the Pope], was a call not merely to guiltless but to meritorious violence."1 Later, Protestants unleased violent forces that perhaps nobody could have predicted. Estimates vary, but the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) decimated central Europe with disease, famine and war that brought early death to at least 15–20 percent of the population—barbarism and butchery in the name of God.

|

Becky Fischer in Jesus Camp. |

Watching the new documentray film Jesus Camp brought to mind Duffy's depiction of "meritorious violence." Jesus Camp features the Pentecostal children's minister Becky Fischer of Missouri, but by including footage of Ted Haggard, president of the National Association of Evangelicals, the film directors clearly intend to include the 30 million people of the Christian right. I physically squirmed in my seat watching these people (re)define the Gospel in endless ways—young earth, intelligent design, abortion, global warming, Harry Potter, home schooling, and fidelity to George Bush—except for the one that Jesus said mattered most—loving your neighbor.

I'm not sure that I could make nice with the KKK like Will Campbell, or that what he did was either good or wise. But I sense that he was pointed in the right direction, a direction commended by Saint Maximos the Confessor (580–662): "Blessed is the one who can love all people equally...always thinking good of everyone." Given my visceral reaction to Jesus Camp, I clearly have a lot of room for improvement.

For further reflection

* Consider the ways that we displace the central command to love our neighbor with peripheral concerns.

* In what sense have social liberals like Campbell and conservatives like Fischer made the same mistake?

* What are some of the legitimate concerns of the Christian right?

* See Must Christianity Be Violent?: Reflections on History, Practice, and Theology, by Kenneth R. Chase and Alan Jacobs

[1] NYRB, October 19, 2006, pp. 41f..