Naaman and Gehazi

The Outsider In, the Insider Out

For Sunday February 12, 2006

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

2 Kings 5:1–14

Psalm 30

1 Corinthians 9:24–27

Mark 1:40–45

|

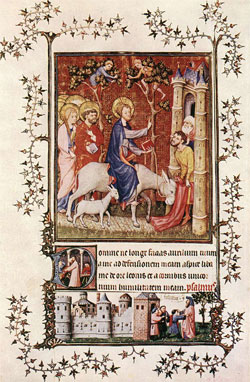

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, by Andreas Heidrich |

Last week one of my five siblings chose not to attend my mother's funeral. After his divorce my brother married an African-American woman and he fretted whether our little church in small-town North Carolina would welcome them. I don't know if he was wise and perceptive in this regard, or projected his insecurities onto others, but the threat of exclusion and marginalization as an "outsider" is a potent toxin for most all of us. No one wants to be an outsider.

In his book The Faith of the Outsider; Exclusion and Inclusion in the Biblical Story (2005) the Old Testament scholar Frank Spina makes a "close reading" of this insider-outsider motif in the Bible. He begins with the unpopular reminder that it is impossible to ignore the presence of what scholars call the "scandal of particularity" throughout Scripture. In the Old Testament, Israel alone is God's elect people: "You only have I known of all the families of the earth" (Amos 3:2). Israel is not only God's special insider community; as Spina notes, "it is the only insider community." All other nations need not apply. Similarly, in the New Testament the early Christians proclaimed that "no one comes to the Father except through Jesus" (John 14:6). If you excised this insider theme from the biblical narrative you would end up with a slender Bible indeed.

|

Naaman washes in the Jordan River, 12th century Germany. |

But that is only part of the story, and one that is significantly enriched by other elements of the plot. When God elected a single community, Israel, His intentions were categorically universal in scope, that in Abraham "all peoples on earth will be blessed" (Genesis 12:3). Those same early Christians who proclaimed Jesus as the only way also imagined heaven populated with "a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language" (Revelation 7:9). When we read the Bible carefully we notice how often it features prominent outsiders. This inclusion of outsider stories, Spina argues, is "neither incidental nor haphazard in the biblical witness." These outsider stories often include a significant plot reversal in which the ostensible insider is cast in a negative light and the outsider is portrayed as superior in virtue or faith. In his book Spina considers seven of these stories where the outsider is mainlined and the insider is marginalized—Esau, Tamar (incest), Rahab (a whore), Jonah, Ruth (a resident alien who remarries a Hebrew), the woman at the well in John 4 who had married five times, and then the lectionary passage for this week about Naaman in 2 Kings 5.

|

The Cleansing of Naaman by the Prophet Elisha, Master of the Baptist, c. 1409. |

Naaman epitomizes the quintessential outsider for several reasons. He was from pagan Aram (= Syria), a military officer of a major enemy of Israel. The narrator praises Naaman in glowing terms: "He was a valiant soldier, a great man in the sight of his master and highly regarded." Then he ads a stunning detail that makes you wonder what he was thinking: "through Naaman the Lord had given victory to Aram." God gave victory to Israel's enemy through a pagan officer? Yes. Finally, Naaman had a skin disease (often wrongly translated as "leprosy"). This disease, as Spina notes, might have caused Naaman some medical problems, but his real complications were social, religious, and moral, for people with such "impurities" were stigmatized as ritually unclean and therefore excluded from God's community and its worship.

Consider a contemporary analogy. "Saddam was an Iraqi military general, praised by all as a valiant warrior and a great man. In fact, the Christian God had granted victory to Iraq through Saddam." This is not where the story of Naaman ends, but it is definitely where it begins.

In search of healing, this "great man" (2 Kings 5:1) embarked on a state visit with opulent gifts to visit the king of Israel, a letter of commendation in hand, only to encounter a nameless "little girl" from Israel who advised him to seek healing from the Hebrew prophet Elisha. The irony is unmistakable and Naaman's response is predictable; when this anonymous Hebrew child instructed the renowned military officer not to seek help from the corridors of political power but from a religious prophet who told him to wash himself seven times in the Jordan River, he was incensed. But Naaman obeyed, he was healed, and then the plot thickens when he was also converted: "Now I know that there is no God in all the world except in Israel." Finally, he made a curious request to take dirt from Israel back to Aram, "for I will never again make burnt offerings and sacrifices to any other God but the Lord." Perhaps Naaman wanted to establish a portable "sacred space" back home? Although back home in Aram he continued to assist his master to worship in the temple of the deity Rimmon, Naaman asked for advance forgiveness for that compromise, and declared his fidelity to Israel's Yahweh.

|

Elisha, oil and collage on canvas by Richard McBee (1999). |

Naaman the outsider joined the insider community, a nameless little girl advised a great man, and the prophetic power of Elisha subverted social and political conventions. The story ends with a tragic reversal when greed overtook Elisha's servant Gehazi. He connived to obtain the gifts that Naaman had offered to Elisha but which Elisha had refused. Gehazi, the insider of Israel's prophet Elisha, was then struck with the skin disease that originally afflicted the outsider pagan military commander Naaman. "The story that began with this disease ends with it," writes Spina, "with the difference that its victims have been reversed: the Aramean outsider has become clean, and the Israelite insider has become unclean."

In a word, presumption is the besetting sin and chronic temptation of the insider. To our peril we ignore, shun, and vilify the outsider as strange, dangerous and unclean. We smugly imagine that we possess the truth as few others do, rather than humbly ask God in His mercy that we might be transformed by His truth. Rather than considering solidarity with the lost, the lonely, and the outsider a privilege that enriches our lives, we construe the Biblical narrative in a narcissistic manner to serve our own petty ends.

The insider-outsider dynamic operates at many levels. My brother experienced it as racism. Ethnicity, an "important" job, a prestigious school affiliation, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, gender, age (consider how our society demeans the elderly), body image, and politics are all identities we embrace, personas that we construct, to comfort ourselves that we are insiders and to scape goat others as outsiders. Tragic self-delusion is never far away: "God, I thank you that I am not like all other men" (Luke 18:11).

|

Elisha, c. 1329, Pietro Lorenzetti, tempera and gold leaf on panel. |

Others we actively "erase" since they do not interest us, or we do not consider them important enough to merit our attention. Ralph Ellison (1914–1994) masterfully portrayed this dynamic in his novel Invisible Man (1952). The young, nameless black protagonist astutely observes how others refuse to see him: "I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me."

Twenty years ago I had a friend who told me that his mother had married five times. At first I thought Mike was kidding, and I tittered with nervous laughter. When I realized that he was serious I blanched at my insensitivity. Would that I had instead emulated the apostle Paul, the consummate Christian insider, who in the epistle for this week contemplates the real and harrowing possibility of his own banishment to outsider perdition (1 Corinthians 9:24–27).

For further reflection:

* When have you experienced exclusion and/or inclusion? What factors were at play?

* Who is the most loving person you know?

* Consider other Biblical stories on this theme like the Good Samaritan or the six other stories that Spina treats.

* For further reflection: Frank Anthony Spina, The Faith of the Outsider; Exclusion and Inclusion in the Biblical Story (2005), and Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation by Miroslav Volf.