Surely He Could Have Prevented This?

For Sunday March 13, 2005

Fifth Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A) hotlink: )

Ezekiel 37:1–14

Psalm 130

Romans 8:6–11

John 11:1–45

|

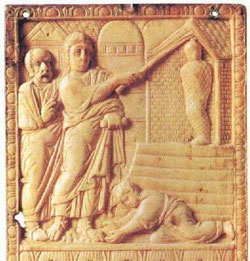

Raising of Lazarus, ivory carving, 400 AD, New Zealand |

Two weeks ago this Sunday, Jill, aged 27, crawled over the side of San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge and plummeted to her death. The son of a close friend of mine was with Jill's husband, Gary, when he received the tragic news of his wife's death. Unspeakable pain, and more than enough collateral damage for everyone who loved Jill. You won't read about her death in the paper; the San Francisco Chronicle avoids publishing stories like Jill's in order to discourage copy cat suicides. But they do report that about forty people a year kill themselves by leaping from that famous bridge that is surrounded by such spectacular scenery.

Jill ran with a crowd that favored trench coats, black leather, metal piercings, and tattoos. She was estranged from her parents, suffered depression, and battled chronic health problems. Her husband Gary is unemployed. But as pastor Craig Barnes writes, no matter what your station in life, "heartache can, and will, find every address. It is only a matter of time," he writes "before all of the violence and heartache of the world comes for a visit."

As I thought about Barnes's observation, my mind scrolled through the emotional wringers that squeezed four other friends this week. Susan will finally tell her siblings and aging parents that her son is gay. Others worry about an alcoholic parent who hit the bottle again after years of sobriety. Yesterday a woman in her seventies told my wife, "Sometimes I hate my husband. Even my kids tell me I should divorce him." Finally, there is Collin, whom I visit a couple of times each week. He has been hospitalized for five months after a brain bleed that left him in a deep coma for six weeks. He came out of the coma (a miracle, according to doctors) but suffers severe physical and neurological damage.

When heartache visits us, as it surely will, nothing is more instinctually human than for the questions to fly fast and furious. Parents ponder whether and how they might have done a better job raising their children. Alcoholic loved ones cause us to wonder about the ambiguous borderlines between genetic sickness and human responsibility, between our enabling complicity or unconditional acceptance. Suicides can generate guilt, conflict, and regret. Spouses facing chronic illness understandably experience anxiety about finances, young children, a looming future, and the sheer emotional and physical energy it takes to keep all the family plates spinning. So, we query ourselves and others who have been sucked into our vortex of pain.

Icon of raising Lazarus from the dead |

We also question God. Questioning God might sound sacrilegious, but there is plenty of Biblical precedent for it. Job harangued God about his personal catastrophe. The prophet Habakkuk begged to know why God looked upon evil and appeared to do nothing. The Psalmists complain about the apparent silence of God. But there is one question in particular that often rises to the surface that we ask of God, and it is a question that our Gospel passage for this week asks not once but three separate times: could He not have prevented our own private hells?

When her brother Lazarus took sick, Mary went to Jesus for help. By the time they finally arrived back home in Bethany, Lazarus had been dead and buried for at least four days. "Lord," Martha cried, "if you had been here, my brother would not have died" (John 11:21). Mary her sister said the exact same thing: "Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died" (John 11:32). Amidst all the grief and tears, the neighbors could not help but mumble their own aside: "Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?" (John 11:37). Could he not have prevented all this horrible pain and heartache we see in front of us?

Jesus did not answer their question. Rather, in the shortest verse in the entire Bible He demonstrated one of the most important characteristics we can ever learn about the heart of God: "Jesus wept" (John 11:35). When Jesus experienced the sisters Mary and Martha weeping for their dead brother Lazarus, and their distraught neighbors, we read that he was "deeply moved in spirit and troubled" (John 11:33). The God whom Christians worship is not a remote and aloof "sky god" somewhere way out there. No, He is a tender God deeply moved, even grieved, by anything and everything that threatens our human well-being.

This compassionate and empathetic character of God is precisely why the Scriptures encourage us to bring to Him every anguish, confusion, anger, perplexity, and anxiety. When my friend Luke lost a second child in a car accident, I remember at the memorial service how he resonated with the Hebrew Scriptures where the saints threw dust in the air and cried out in pain. Like Mary, Martha, and their neighbors, the Psalmist for this week demonstrates just this sort of visceral scream to God (Psalm 130:1–2):

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord;

O Lord, hear my voice.

Let your ears be attentive

to my cry for mercy.

We can pray like this to God because we know that He weeps when we weep. We place our hope in Him because, as the Psalmist continues, He is a God of "unfailing love" and "full redemption" (Psalm 130:7).

|

Raising of Lazarus, Statesboro UMC Church, Georgia |

God not only empathizes with our many weaknesses. He also acts. Jesus wept with Mary and Martha, and then he raised Lazarus from the dead. Of course, human experience tells us that God does not act exactly when, where, and how we think He should act. So we are left to wait in hope. The Psalmist cries out to God with full confidence in His compassionate love, but even so He also says five times, perhaps talking to himself, that he must "wait" (Psalm 130:5–6).

Part of Christian maturity involves learning to wait, confident not so much about our chances for a rosy outcome, or about exactly where, when and how God will act, but confident that He will act. We wait in hope even while we "cry out of the depths" to God. The alternative is to lose hope and to spiral into despair, which I suspect is what happened to Jill. We also read about such hopelessness in the Old Testament reading for this week: "Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off" (Ezekiel 37:11). However tempting, however human, however understandable, hopeless despair is not a Christian place to live.

Winter will not last forever; spring will come. Lenten darkness, repentance and sorrow have their rightful place with us, but Easter resurrection is our destiny. However painful our current circumstances, and however agonizing our honest questions—about job loss, wayward children, financial disaster, chronic sickness—ultimately things will get worse, for nothing can compare to the horrible specter of death that awaits us all. But Christian faith believes that God in Christ will conquer and transform even that ultimate enemy death. For the time being, then, we confidently "cast every anxiety upon him, because he cares for us" (1 Peter 5:7).