Book Notes

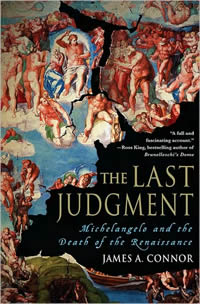

James A. Connor, The Last Judgment; Michelangelo and the Death of the Renaissance (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 233pp.

James A. Connor, The Last Judgment; Michelangelo and the Death of the Renaissance (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 233pp.

Many of us who think of Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475–1564) remember his famous fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel that depicts the creation account in Genesis, and his marble statue of David, a seventeen foot colossus of the Biblical king in a triumphantly nude pose of the perfect human specimen. James Connor's book examines Michelangelo's other great fresco, The Last Judgment, painted on the western altar wall of the Sistine Chapel almost thirty years after he finished the ceiling.

Michelangelo started work on The Last Judgment in 1536 when he was sixty-one, and completed it five years later when it was unveiled on Christmas Day 1541. Measuring forty-six by forty-three feet, the work covers 1978 square feet and contains 456 giornate or individual plaster sections. Like much great art, the fresco was the subject of immediate critical controversy, and even censored by the Council of Trent, which demanded that parts of it be repainted. One figure depicts an avaricious pope with a set of keys and a bag of gold. Another shows a man dragged into hell by his testicles. Energy and anxiety radiate from the swirl of supplicants, both saved and damned, encircling Christ the Judge. Encoded into the painting is the heliocentrism of Copernicus, and a likeness of Michelangelo himself.

Connor does a wonderful job of combining history, art, theology and biography into an uncluttered narrative. He situates the work in the context of the tumult of Renaissance Italy and the sack of Rome in 1527, the Protestant Reformation that was convulsing Europe, and the unfolding currents of the Catholic Counter Reformation. He introduces a colorful cast of characters — the popes, of course, but also the ascetic reformer Savanarola who was eventually hanged and burned, Michelangelo's male love Tommaso Cavalieri, female friend Vittoria Colonna, the bawdy pornographer and trouble maker Aretino, and his long-time assistant Urbino. I especially enjoyed his explanation of the nature and techniques of buon' fresco in which the artist applies pigments to wet (as opposed to dry) plaster.

The Last Judgment is not only a great work of art, it is also a theological confession by Michelangelo, for whom, according to Connor, all his painting, sculpture, architecture, and poetry were his own deeply personal prayers (p. 122). It's clear that the epitome of the so-called "Renaissance Man" asks himself, "where will I be on that Great Day?" and that he challenges every person who engages it, "And what about you?" A short bibliography "for further reading" completes the book. My only disappointment is that the book contains only a few black and white reprints, and not full color plates that a book and fresco like The Last Judgment deserve.