Book Notes

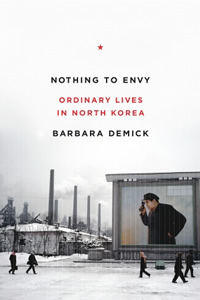

Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy; Ordinary Lives in North Korea (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2010), 319pp.

Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy; Ordinary Lives in North Korea (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2010), 319pp.

Barbara Demick, the Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, moved to Seoul in 2001 for her newspaper, and across the next seven years made nine trips into North Korea. This oral history of the world's most oppressive and secretive regime is organized around the stories of six North Koreans who defected to South Korea, and is richly supplemented by her interviews with over a hundred people, personal study, and interactions with NGOs, government analysts, and various exiles. The result is a stunning portrait of a bizarre dictatorship that has brutalized its 23 million citizens.

A satellite photo of the Korean peninsula at night shows South Korea ablaze with lights and then, as if someone drew a line with a ruler at the 38th parallel, North Korea ink black except for the tiny dot of Pyongyang. This is a country where public displays of affection like holding hands are prohibited, international aid workers are not allowed to study Korean, the internet does not exist, doctors operate in hospitals without electricity, heat, water, or antibiotics, schools have no books or paper, postal workers burn the mail for heat, attendance at public executions is compulsory, history is reinvented wholesale, religion is forbidden, 200,000 citizens languish in labor camps, people step over dead bodies in the street, and, in the late 1990s, upwards of two million people died in a famine — all thanks to the Great Leader Kim Il-sung (1912–1994) and his son Kim Jong-il (born 1941).

Things were not always so bad. For 1300 years Korea existed as a single entity. After thirty-five years of Japanese occupation (1910–1945) and at the end of the war, the western powers drew a line across the thirty-eighth parallel without any basis in culture or history, effectively giving the north to the Soviet empire and the south to the west. For many decades the north fared better than the south, but the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and China stranded North Korea without its major benefactors. Since they produced almost nothing and could not afford to buy anything, wholesale disaster followed. A kindergarten teacher watched her students die in front of her and her class size shrunk from fifty to fifteen. A doctor had little more than a stethoscope. Starving citizens gathered grass, bark and weeds in the woods for food. Surveillance is omnipresent.

The title for the book is a biting double entendre based upon a song that every school child memorizes:

Our father, we have nothing to envy in the world.

Our house is within the embrace of the Workers' Party.

We are all brothers and sisters.

Even if a sea of fire comes toward us, sweet children do not need to be afraid,

Our father is here.

We have nothing to envy in the world.

But when starving people catch furtive glimpses of South Korean television, or experience the riches of goods when they cross the border into China, experiential truth deconstructs a lifetime of lies. "Open your eyes!" shouts Oak-hee at her mother. "You'll see our whole country is a prison. We're pitiful. You don't know the reality of the rest of the world." The great mystery bandied about by experts, says Demick in her final pages, is how and why the hermit kingdom can continue to exist.